Why Leadership Is Revealed, Not Chosen

The Myth of the “Leadership Style”

Most leaders can explain how they like to lead. Far fewer can explain how they actually lead when things turn uncomfortable.

That is because leadership is rarely a conscious choice in the moments that matter. It shows up through decisions made under pressure, when time is short, information is partial, and the cost of hesitation feels higher than the cost of being wrong. In those moments, language disappears. What remains is instinct.

I have watched leaders who spoke convincingly about empowerment take control the moment delivery slipped. I have seen collaborative leaders bypass discussion when risk reached the board level. Not because they lacked integrity, but because pressure reveals patterns that intention alone cannot override.

This is why most leadership frameworks feel persuasive in theory and thin in practice.

Pressure Exposes Defaults

Calm environments allow leaders to operate close to their ideals. Pressure pushes them toward their defaults.

When deadlines tighten and consequences sharpen, behaviour becomes predictable. Some leaders move faster and narrower. Some pull decisions inward. Some seek reassurance through agreement. Some take the weight onto themselves. None of these responses are accidental.

Over time, teams learn these patterns. They adjust how they escalate issues, how much initiative they take, and how safe it feels to challenge decisions. Long before culture is discussed explicitly, it has already been shaped by these repeated signals.

This is how leadership leaves a lasting imprint without ever announcing itself.

How to Read What Follows

This article is not about finding the right type of leader. It is about recognising the one you become most often.

The seven leadership types that follow are not personality profiles. They are behavioural patterns formed by incentives, risk, and experience. Each one can be effective in the right context. Each one creates problems when it becomes automatic.

If this feels uncomfortable at points, that is intentional. Senior leadership is less about adopting new ideas and more about noticing what you already do, especially when the pressure is on.

The Operator: Execution Above All Else

Decisions First, People Second

Every organisation needs an Operator at some point. This is the leader who turns uncertainty into movement. Decisions are made quickly. Deadlines are met. Standards are clear and non-negotiable. When others are still discussing options, the Operator is already executing.

This posture is often rewarded early. Work moves. Clients stay satisfied. Senior stakeholders see progress. The organisation learns that things get done when this leader is involved.

The cost emerges more slowly.

Operators tend to prioritise output over capacity. They notice slippage faster than strain. Under pressure, they narrow focus and increase pace, often without recognising how that intensity lands on the team. Over time, people adapt. They stop flagging overload. They solve problems quietly. They avoid becoming friction in a system that values speed above all else.

Standards remain high, but ownership contracts. Teams execute well yet hesitate to take initiative. Risk-taking becomes cautious. Leadership stays centralised, even as the organisation grows.

I have seen Operators genuinely surprised when capable people leave. From their perspective, expectations were clear and results were delivered. What they missed was the cumulative impact of always leading with urgency, even when urgency was no longer required.

The Operator is essential in moments that demand clarity and momentum. The risk is remaining there by default. When execution becomes the only leadership language, resilience and long-term growth quietly weaken.

The Protector: Carrying More Than Your Share

The Leader Who Absorbs Risk

The Protector leads with responsibility. When pressure rises, they step forward rather than push decisions downward. They shield their teams from politics, absorb uncertainty, and take accountability when things go wrong. For the people around them, this creates a strong sense of safety.

Loyalty forms quickly under this style of leadership. Teams trust the Protector because they feel defended. Conflict is managed. External noise is filtered. People can focus on their work without constantly looking over their shoulder. In unstable or high-risk environments, this posture can stabilise an organisation that would otherwise fragment.

The problem is not the instinct to protect. It is how long the protection lasts.

Over time, teams adapt to the presence of a leader who carries more than their share. Decisions drift upward. Risk awareness dulls. People wait to be shielded rather than learning how to navigate exposure themselves. What began as care slowly turns into dependency.

I have seen Protectors become overloaded while their teams remain underdeveloped. They attend every difficult meeting, resolve every conflict, and absorb every consequence. From the outside, they look indispensable. From the inside, the organisation stops growing up.

The most dangerous moment for the Protector is not burnout, though that often comes. It is the point where the leader’s absence would create paralysis. At that stage, loyalty is real, but resilience is not.

Protection is powerful when it is temporary and deliberate. When it becomes permanent, it quietly limits capability, judgement, and ownership across the organisation.

The Vision Carrier: Living in the Future

Always Pointing Forward

The Vision Carrier leads through belief. They give people a sense of direction when the path is unclear and energy when momentum is fading. In uncertain environments, this can be transformative. Teams move because they believe in where they are going, not just in what they are doing today.

This type of leader is often at their best during periods of change or growth. They connect individual effort to a larger story. They create meaning beyond targets and timelines. People follow because the future feels compelling and worth the discomfort of transition.

The risk lies in how consistently the future is prioritised over the present.

Vision Carriers tend to defer operational friction. Missed targets are reframed as temporary. Structural weaknesses are tolerated in service of speed. Hard conversations are postponed because they do not fit the narrative of progress. Over time, reality accumulates in the background.

I have seen organisations scale belief faster than capability. Teams stay optimistic even as systems strain, costs rise, and accountability blurs. The longer these signals are ignored, the more expensive they become to correct. What once felt like momentum eventually turns into rework, attrition, or loss of credibility.

Vision does not fail because it is wrong. It fails because it is insufficient on its own.

The Vision Carrier is most effective when belief is matched with discipline and attention to present constraints. When the future becomes an escape from current responsibility, the organisation pays for it later, often all at once.

The Consensus Builder: Safety Through Agreement

Nothing Moves Until Everyone Is Comfortable

The Consensus Builder leads with inclusion. Decisions are shaped through discussion, alignment, and shared ownership. People feel heard. Dissent is invited. In environments where trust is fragile or history is bruised, this approach can repair damage and restore engagement.

At its best, consensus creates commitment. When people help shape decisions, they are more likely to support them. The organisation feels fair. Risk is surfaced early. Power is distributed rather than concentrated.

The difficulty is that agreement becomes a prerequisite rather than an outcome.

Consensus Builders often struggle with discomfort. When opinions diverge, decisions slow. When accountability sharpens, language softens. The desire to maintain harmony quietly overrides the need for clarity. Over time, teams learn that nothing moves until everyone feels safe enough to agree.

Momentum fades in subtle ways. Opportunities are missed while alignment is sought. Urgent decisions are reframed as complex. Strong views are moderated before they can be tested. What looks like patience from the inside feels like hesitation from the outside.

I have seen capable organisations stall not because of lack of talent or intent, but because no one wanted to be the person who disrupted agreement. Leadership became facilitation rather than direction.

Consensus is valuable when stakes are high and time allows for deliberation. It becomes damaging when speed and decisiveness are required. When harmony is mistaken for leadership, progress slows, and the organisation quietly learns to wait.

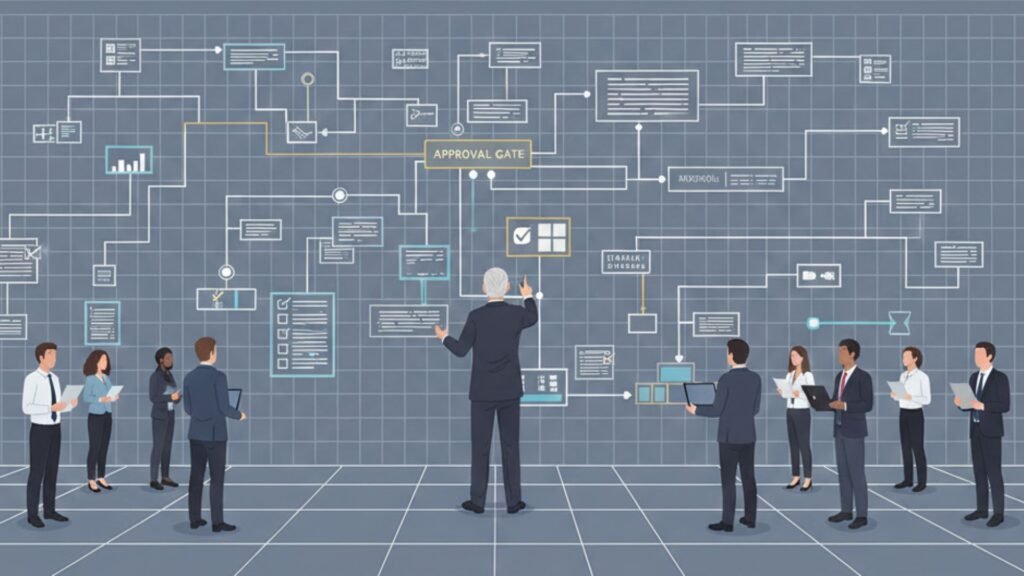

The Controller: Standards Without Trust

Precision, Discipline, and Diminishing Autonomy

The Controller leads through precision. Expectations are exact. Processes are defined. Quality is enforced through close oversight. In complex or regulated environments, this can prevent serious failure. Mistakes are caught early. Variability is reduced. Outcomes are predictable.

Controllers are often highly capable themselves. They know what good looks like and are unwilling to compromise. When pressure rises, they lean harder into detail, review, and control. From their perspective, this is responsibility, not micromanagement.

The tension appears as teams mature.

As oversight increases, autonomy shrinks. Capable people begin to feel managed rather than trusted. Decisions funnel upward. Initiative becomes risky because deviation invites correction. Over time, strong performers stop stretching. They do what is required, no more and no less.

Excellence turns into a bottleneck.

I have seen Controllers surrounded by talented teams who wait for approval on decisions they are fully qualified to make. The leader becomes the constraint, not because of lack of effort, but because everything must pass through their hands. What once ensured quality now slows progress.

The Controller rarely notices disengagement at first. Output remains high. Standards are met. What disappears is ownership, creativity, and leadership depth beneath them.

Control is effective when competence is uneven or consequences are severe. It becomes corrosive when it replaces trust. Without deliberate release, discipline sustains performance while the organisation quietly stops growing leaders.

The Firefighter: Thriving in Chaos

Excellent in Crisis, Invisible in Calm

The Firefighter comes alive when things go wrong. They cut through confusion, take charge, and stabilise situations that feel out of control. In moments of genuine crisis, this leadership is invaluable. Decisions are made quickly. Priorities are clear. People know who to follow.

Firefighters earn credibility through rescue. They are remembered for fixing what others could not. When pressure peaks, they deliver.

The problem is what happens between crises.

Firefighters tend to disengage when systems are stable. Preventative work feels dull. Process improvement lacks urgency. Planning is deprioritised because it does not produce immediate relief. Over time, the organisation learns that attention only arrives when something breaks.

Urgency becomes a currency.

I have seen teams unconsciously allow problems to escalate because escalation is the only way to get decisions made. Minor issues are left to grow until they justify intervention. Dysfunction becomes structural, not through incompetence, but through learned behaviour.

Firefighters rarely intend this outcome. They genuinely care about solving problems. What they underestimate is how strongly organisations adapt to leadership signals. When crisis is the moment leadership appears, stability is quietly neglected.

The Firefighter is essential when failure is imminent and speed matters. The risk is building an organisation that depends on chaos to function. When calm feels unimportant, resilience never forms, and the next crisis is always waiting.

The Self-Aware Leader: The Only One Who Adapts

Not a Type, a Posture

The self-aware leader does not arrive with a fixed style. They arrive with an understanding of their own defaults.

They know how they behave when pressure rises. They recognise the moments when they become faster, narrower, more protective, more controlling, or more avoidant. Most importantly, they notice these shifts while they are happening, not months later during a post-mortem.

This awareness creates range.

Instead of reacting automatically, the self-aware leader chooses how to respond based on context. They know when to push for speed and when to slow the system down. They can protect a team without creating dependency, set standards without suffocating initiative, and seek input without surrendering direction.

This posture is not about balance for its own sake. It is about matching leadership behaviour to the actual needs of the organisation at that moment.

I have seen leaders evolve dramatically once they understood their default under stress. The change was not dramatic or performative. It showed up in small, consistent adjustments. Decisions were delegated earlier. Silence was used more deliberately. Discomfort was tolerated rather than avoided.

Teams respond quickly to this shift. Trust deepens because behaviour becomes predictable in a different way. People understand when control will appear and when autonomy is real. Leadership stops feeling personal and starts feeling intentional.

The self-aware leader is not the absence of the other six types. They are the leader who can access them without being trapped by any single one. That is what maturity looks like at senior levels.

Leadership does not improve by adding more tools. It improves when leaders recognise themselves clearly enough to choose differently under pressure.

What Experienced Leaders Do With This Insight

You Don’t Eliminate Your Default. You Manage It.

Every leader has a default pattern. It shows up under pressure, when decisions feel exposed and time feels compressed. The mistake is believing maturity means replacing that pattern with a better one.

It does not.

Experience teaches you that defaults do not disappear. They resurface when stakes rise. The difference at senior levels is not self-reinvention. It is self-management. Leaders who last learn to recognise their instinct early enough to moderate it, rather than apologising for it later.

Self-awareness beats ambition every time. You do not need a new leadership identity. You need a clearer view of the one you already inhabit when things get hard.

Context Determines Which Type Works

None of the leadership patterns described earlier are inherently flawed. Each one works in the right moment.

Speed matters during crisis. Protection matters when teams are exposed. Control matters when consequences are severe. Vision matters when direction is lost. Consensus matters when trust is thin.

The problem begins when a leader applies the same posture regardless of context. Organisations move through phases. Risk profiles change. What worked during growth can fail during scale. What stabilised the business last year can constrain it this year.

Experienced leaders stop asking, “What kind of leader should I be?” and start asking, “What does this situation actually require?” That shift alone prevents many avoidable failures.

Leadership range is not about versatility for its own sake. It is about accuracy.

The Quiet Test of Senior Leadership

There is a moment in every senior leader’s career when the rewards change.

Early on, you are praised for saving the day. For stepping in. For fixing what others could not. Over time, that praise becomes a trap. The organisation starts to rely on your intervention rather than its own capability.

The quiet test of senior leadership is whether things work without you being visible. Whether decisions are made without escalation. Whether problems are solved before they reach your desk.

This is uncomfortable for leaders whose identity was built on being essential. It requires restraint rather than effort. Patience rather than action.

At the highest levels, leadership is less about being impressive and more about being deliberate. The strongest signal you can send is not that you can handle everything, but that the organisation no longer needs you to.

That is when leadership has truly taken root.